Digitisation and the role of newspapers in European public life

Dieser Beitrag ist eine gekürzte Fassung des Essays „Habermas revisited – Why media digitisation spurs on the idea of creating a new European public sphere“ von Perlentaucher-Gründer Thierry Chervel, BuzzFeed-UK-Medienredakteur Patrick Smith und Peter Littger, Vorsitzender der King Edward VII British-German Foundation. Er ist ursprünglich in dem Buch „Common Destiny vs. Marriage of Convenience: What do Britons and Germans want from Europe“ erschienen.

Dieser Beitrag ist eine gekürzte Fassung des Essays „Habermas revisited – Why media digitisation spurs on the idea of creating a new European public sphere“ von Perlentaucher-Gründer Thierry Chervel, BuzzFeed-UK-Medienredakteur Patrick Smith und Peter Littger, Vorsitzender der King Edward VII British-German Foundation. Er ist ursprünglich in dem Buch „Common Destiny vs. Marriage of Convenience: What do Britons and Germans want from Europe“ erschienen.

No traditional medium born into the analogue world has been spared the upheavals wrought by digital media. The production, consumption and reception of all journalistic genres can be viewed through the conceptual lens of ‘disruption’ – a much-vaunted notion that sprang from the digital revolution. It describes products and procedures, which unexpectedly alter the nature of the entire marketplace, such as Youtube, Facebook, Twitter, Buzzfeed and email and SMS. Many of them appeared only a few years ago – but they have seized great portions of our time (and financial) budgets and often feel as if they have been around for ages.

The tragic side to all this is that in the digital domain journalism with a soul is not being given its due respect and is, in overall terms, seen as being more workmanlike. Outside the arena of public service providers, journalism is being subjected exclusively to commercial criteria – and perhaps this is to be expected. But even if we were to apply a value-neutral assessment and use the term ‘content’ for journalistic material, (here, Germans also employ the English word ‘content’) the term implies in and of itself a range of products that can be conceived, produced and scaled at will.

Content is not the highest priority

This is, of course, not the case. Particularly successful strains of journalism exhibit something of the inimitable – a something that cannot be mass-produced. The reality of the digital media landscape is that meaningful, attractive, educational – in short ‘high-end’ (Germans are fervent about the term ‘Qualitätsjournalismus’) – content does not enjoy the highest of priorities. That is because in the development of these digital media it has been the underlying technology that has been construed as the prime determinant in making these start-ups profitable in order to sell them on.

Mathias Döpfner, CEO of Europe’s biggest newspaper group, Axel Springer, pointed out: “Over the past 15 years, content models have been neglected. In Silicon Valley, there was hardly anything so unsexy as content”. Döpfner may well be expecting a “major surge in content models” as well as a ‘rediscovery of content in the digital world’ – but executives and editors from the Axel Springer group still have not been able to explain how to make ‘high- end’ or ‘quality’ journalism with a soul profitable in this brave new world or at least earn sufficient money to uphold sound editorial teams.

Across the web, there may well be some isolated commercial success stories to report but, overall, it is not obvious quite how standalone journalistic texts can generate enough income outside the model of the traditional newspaper set-up just described. In other words: there may be digital content formulas appealing to consumers, but they will have to stand out considerably from the journalism we are talking about if their managers want to be successful in the market.

The scenario is best illuminated through the example of music downloads. An individual can purchase a song file with a view to listening to the track more than once. The song is a consumer good that does not break like a pair of sunglasses, melt like ice cream or age like a telephone set. it exists forever – possibly, if it is great in our minds and our playlists.

Now, a good piece of journalism may not break, melt or age, but (despite its humanistic value) it bears one major disadvantage for the newspaper proprietor: no consumer would wish to read a text over and over again, unless he or she needs to do so for professional reasons, or the article struck a particular nerve with the reader. The average piece of journalism never achieves such an afterlife.

Moreover, we need to ask ourselves just what kinds of people are still reading? It is a relevant question because many of the publishers and editors-in-chief who have been extolling the virtues of paywalls have also been painting the picture of a society ever more eager to read, even of a society in thrall to profound background information and the humanities (Geisteswissenschaften). We, however, have observed the opposite happening: texts in the digital world are being ‘recommended’ at an astonishing rate but are rarely ever read.

Journalism has always been subsidised

In the halcyon days of print, publishers used to be canny – they were aware that their main product was not the journalistic material itself, but rather a package containing also advertising and classifieds – and it was this package that constituted their bestseller. But the business model has ceased to function as it once did – it has, over time, lost its erstwhile function. Much of the blame for this state of affairs lies with the altered structure and financial viability of advertising that once made the whole newspaper package viable.

Of course, consumers used to buy newspapers because they were a delivery platform for information – but they were also instruments that aided in the organisation of both social life and markets. Readers sought out shop opening hours, theatre listings, job offers and, of course, fell upon all manner of advertising. In sum, newspapers were sustained by functions that are nowadays better performed by the likes of eBay, Facebook and Amazon.

First and foremost it was the classified and commercial advertising sections that financed newspaper journalism. Transient journalistic material was rarely profitable in and of itself. There exists no business model for the provision of information that serves both society and a meritorious purpose as well. Journalism had always benefited from a sort of internal subsidiarity whereby the advertising oligopoly of the publishers provided the necessary capital for journalistic endeavours. This means that if journalism with a soul is to survive, it will have to undergo a major transformation and bring to the market whole new products that are either highly trustworthy and useful or totally irresistible. Otherwise, journalism as a consumer good is not likely to survive.

The crisis in the newspaper industry is, however, only one symptom of the structural transformation of the public sphere. This transformation does in fact have more far-reaching and profound consequences than Jürgen Habermas described in his 1962 analysis. This transformation pushes all boundaries and affects all media above and beyond publishing, and – as it does so – it even calls into question the term ‘medium’ itself.

Publishers stubbornly hold on to their old models

The lamentable side to all this is that publishers have stubbornly held on to their old products, both printed and digital. This has partly been due to arrogance and partly due to a lack of ideas. Publishers in Germany have attempted to win over parliament in their bid for an ‘ancillary copyright’ law (Leistungsschutzrecht) – otherwise known as the ‘Google law’. We believe this was a bid for a new, publicly constructed pillar of the media system – and in order to achieve this, it would have entailed that practice oft-imputed to bankers: socialising losses while privatising profits.

On the one hand, the ancillary copyright paradigm calls for payments to be distributed when a news aggregator site (like Google) displays text from a news article (thereby linking to the publisher’s own site). On the other hand, the publishers deliberately ignored the fact that they themselves were developing content models that function like aggregators. In a dossier on the current crisis in journalism, Die Zeit’s editor-in-chief Giovanni di Lorenzo described how society’s ‘critical custodians’ were now becoming highway robbers. The publishers’ campaigns look like the last skirmishes of an end game (in a ‘sunset market’, as consultancy jargon puts it) in which they are simply trying to win time, even though they are aware that an outright defeat is inevitable.

In the case of the German proposal for an ancillary copyright law, what we are seeing is sanction instead of innovation. With their position in dispute, newspaper publishers have shown their readiness to surrender the very public-sphere function of journalism that they have always lauded from on high: the free circulation of information. On the other hand, one should not forget that the business model of newspapers was predicated on the notion of a closed, regulated and highly standardised market: where else would advertisers want to show off their wares than in the papers?

Nonetheless, the fact that Germany’s political leaders gave into the demands of the country’s newspaper publishers, despite their weakened position, demonstrates that the papers still have clout.

Good journalism needs public funding to survive

It is our working assumption that media products with a sound journalistic core as we know them today are – by default – not adequately fit to be refinanced, and so suffer from an inherent structural weakness. According to the traditional definition, these journalistic products constitute a public good; this means that if they suffer a commercial (i.e. market) failure, and society deems them to be of import, then public subsidies jump in to sustain them. It is precisely for this reason that the United Kingdom has had public service broadcasting for the past 90 years and Germany has done so for the past 70. In both cases, the general public has to pay for the service because it has – hypothetically – decided to have it and hence is compelled to do so.

Against this background, we are suggesting that we European should focus our efforts on this public service system to create, on the one hand, a new subsidiarity in favour of good journalism with soul and – on the other hand – to harness the enormous innovative energy needed to develop products beyond mere text for a society that is reading less and less, but one that is receptive to them and – ideally – ready to pay for them.

While commercial news media are having to reassess their business models, public service outlets remain cordoned off from the fall-out of the digital revolution. They have deep pockets and are attempting to adapt their model to the demands of the new age. Their problem, though, is that they are suffering a profound crisis of legitimacy.

The internet’s inherent ‚freebie mentality‘

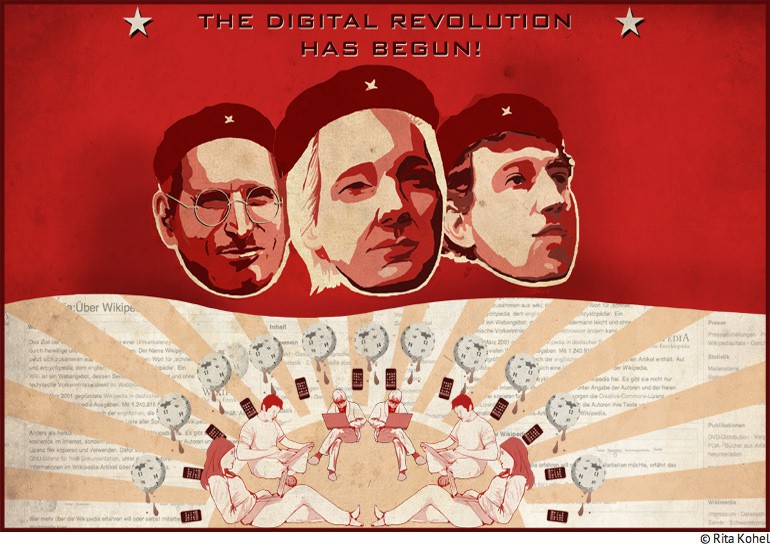

The internet owes its very existence to a grassroots revolution that occurred primarily across the Atlantic. Amongst western nations, the US is something of an oddity: its publicly funded media are less significant than its private media. And it was from the US that the most radical structural transformation of the public sphere since the invention of the printing press was launched. As historian Valentin Groebner recently put it, the internet represents the realisation of hippie ideology. Groebner, however, misses one salient aspect of the story; without the free software movement, the internet would never have seen the light of day. Thousands of programmers and other IT folk – in a collective but not always deliberately conscious act – decided to forego royalties and copyright in order to make the internet take off.

Europeans too have become party to the freebie mentality. They conveniently overlook the aspect of sharing that is an inherent part of the new mindset: had Tim Berners-Lee, Linus Torvalds or the German inventors of the MP3 standard demanded royalties, then it is fair to say that the internet would not have achieved the importance it has. Wikipedia, the free online encyclopaedia spawned by nothing other than civic-mindedness, has demonstrated that relevant information can be collated and published without the need for hierarchical structures.

Public media need to fully embrace the digital

Both Germany and the UK are suffering from a double media crisis; while newspaper journalism is in its death throes and legacy publishers are losing their legitimacy, public service media are squandering an opportunity as well as their entitlement.

In short, European societies should consider how they are to go about restructuring their public sphere as well as how to protect journalism with a soul, and develop it further. In this way, journalism can be – in a guise beyond text – both desirable and service the needs of a democracy. This will require much innovation and we believe that this special, merit-oriented innovation can only be performed when a new internal subsidiarity is adopted as a means of administering the huge budgets currently at the disposal of public media.

We have the impression that the urgency of this debate has not been recognised hitherto. This is partly due to the fact that the old media in Europe have behaved like vested interest groups in order to secure the status quo. At the same time, the intellectual harbingers of the digital revolution and the new self-organising public sphere come from the US – as do the majority of the world’s more successful digital companies.

Journalism is not a typical market commodity

In his seminal book The Wealth of Networks, Yochai Benkler makes a pointed observation: “education, arts and sciences, political debate, and theological disputation have always been much more importantly infused with non-market motivations and actors than, say, the automobile industry”. The more freely these goods are allowed to circulate, the less they are directed by state or market forces – and all the better for it, says Benkler.

Good journalism has always been subsidised. The internet wrecks advertising subsidy. Restructuring is, therefore, a forced move. There are many opportunities for doing good work in new ways.

We in Europe like to see ourselves as something of a rearguard to the US. Indeed, America has seen greater erosion of its old media as well as greater development of innovative media. Nonetheless, many of America’s foremost thinkers on media transformation look upon European nations with awe. They see in their midst the idea of a publicly organised media structure that has been successfully implemented for some time now. This tremendous expertise should now come to the aid of establishing a transnational public sphere of civic and innovative media. It should bespeak a digital structure to protect the public sphere from corporate or state interference – keeping the public sphere concerned with the interests of democracy, free speech and the insights of each and every citizen, including the provision of any relevant data.

The digital revolution has consequences for even the most sheltered strata of society. It creates new forms of the privately constructed public sphere and destroys parts of the existing political public sphere with its attendant norms. All forms of representation and public discourse ultimately change in both positive and negative ways – with new manipulative-paternalistic as well as democratic-participative forms – and they change in myriad directions. Here, we can discern directions that not even Habermas would have dared predict when he wrote about the mass media and the transformation of the public sphere in 1962. Moreover, what we are experiencing right now makes Habermas’s critique a prelude to that which is unfolding today and being accelerated in digital space.

Habermas underscored the determinant position of the enlightenment in the communicative evolution of society. While he made the individual right to participation in discourse something of a norm – and the actual, undirected participation a goal – Habermas directed his vehemence against leftover feudal forms, as well as new, pseudo-feudal forms of communication. They even reflect the high and low points of the European culture of communication – although nowadays it is almost exclusively the US that creates new relevant structures, standards and companies in digital media. Thus, the theory of the ideal public sphere is ultimately a concept predicated on the history and experience of European civilisation. At the same time, facing strong digital innovators across the Atlantic – and their financiers – Europeans realise the difficulties of fulfilling their destiny to shape and animate an ideal public sphere.

Today’s digital public sphere

One communicative moment in today’s digital public sphere propels us on a journey through several thousand years of European communication; that is to say that we relive the participatory aspect of the Greek polis at the same time as we fall foul of the absolutist mannerisms of the 17th century. On the one hand, we are communicating with like-minded people as we once did in the coffee houses of the 18th century – a phenomenon catalysed by social media and not lost on The Economist which carried a feature on ‘the return of the coffee houses’ in 2012. On the other hand, we find ourselves increasingly confronted with a persistent closed-shop mentality in public media and under the yoke of media proprietors – almost as if the horror scenarios of 20th-century press barons and TV moguls have come to pass.

Although it will continue to be the case that not everyone can be accounted for, we can say we have a far more ideal public sphere than existed in the second half of the 20th century, in which the standard is the opportunity to participate more easily in public debates and also to obtain a lot of relevant data that wasn’t available even ten years ago. On the other hand, we don’t see that this new paradigm is being fostered and cultivated enough by legacy publishers, who are going through their death throes, or by public media, who are distinguished by saturation and arrogance (as Britons and Germans raise a combined total public media budget of approx. £11,1/€13,3 billion per year).

This is particularly worrying as the United States, and increasingly other nations in the world, show much more prowess in digital media innovation. It is they who lay the foundations and define the standards for public communication in the digital age – not us! In conclusion, what we want from Europe is for it to stay true to our traditions in quality journalism and civic communication and exploit our diversity and joint expertise much better for creating and financing a truly civic and highly innovative media ecology that serves the needs and responds to the questions of our time.